this time, once again courtesy of 'boromir' another incredibly super rare album.

on the legendary french mouloujdi label.

francois tusques was one of he european pioneers of the genre, who made the transition from a more conventional jazz language sometime in the early 60's.

here is an article from the incredibly useful all about jazz site.

Francois Tusques et le Nouveau Jazz Francais

Published: January 10, 2006

By

Clifford Allen

It is somewhat ironic that, as much as European jazz and free improvisation are nestled squarely within the canon of contemporary music—one has to look only at the worldwide recognition of figures like Germany’s Peter Brötzmann, England’s Evan Parker, or Holland’s Misha Mengelberg and their respective integral scenes—the country with the closest ties to vanguard American jazz in the ‘60s has been almost wholly left out of the picture. France has produced several world-renowned improvisers (for example, clarinetists Michel Portal and Louis Sclavis are among the instrument’s greatest proponents), but the architects of France’s ‘new thing’ have been summarily left by the wayside over the course of the music’s history. Pianist and composer François Tusques, while almost unknown outside his native France, is certainly among the rare few in European jazz, not only as a crucial figure in the development of the music in his sector of the continent, but so crucial that he was able to record the first true French free jazz record (Free Jazz, reissued by In Situ)—a claim which, Stateside, is not even Ornette Coleman’s.

Born in 1938 in Paris, Tusques migrated with his family to rural Brittany shortly thereafter, though as his father was a crucial figure in the French Resistance, François and his family moved around quite a bit during and after the War, eventually spending two years in Afghanistan and another two in Dakar before returning to France. As the potential for danger at being ‘outed’ as a member the Resistance was so high, Tusques did not attend any French schools at the time, for fear that he would accidentally divulge his father’s secret to his peers.

This secretiveness, on top of the fact that his family was so mobile, contributed to a difficult childhood, and despite the fact that his mother was an opera singer, poverty and circumstance kept Tusques from beginning musical training until he was eighteen, when he began to study the piano. “I had only one week of lessons; after that, I was on my own—you could say an ‘autodidact.’ I learned to play mostly by ear, especially from the drummers.”

Tusques quickly took to jazz—his worldliness certainly offering exposure to sounds that he would not have heard otherwise during the War—and counts among his early favorites Bud Powell and Rene Urtreger, not to mention subsequent affinities for Cecil Taylor (“but I am not a technical pianist…” says Tusques), Mal Waldron, Monk and Jaki Byard. At the start of the 60s, there was a significant scene of American expatriate improvisers in Paris—Bud, Dexter Gordon, Kenny Clarke, and traditionalists like Bechet—and a handful of young French players ready and willing to sit in, like saxophonist Barney Wilen and bassist Pierre Michelot. Certainly, as in England and elsewhere in Europe, French jazz of this nascent period was almost entirely beholden to the American post-bop model, and quite a few players who could stand alongside their American peers and run the changes.

Nevertheless, there was also a coterie of French improvisers for whom American-derived bebop was not the end, if even the means. Composer, arranger and sometime pianist Jef Gilson (who eventually began the famed Palm Records) was one of the ringleaders of the Parisian new jazz scene, mentoring young players like trumpeter Bernard Vitet, tenorman Jean-Louis Chautemps, drummer Charles Saudrais, bassist Beb Guerin and other soon-to-be leading lights. Tusques, though, was the only pianist at the time in Paris willing to extend those steps into the demanding compositional sound-world of ‘free jazz,’ and those who saw a continuous upward- and outward-mobility with this music looked to Tusques as a fulcrum.

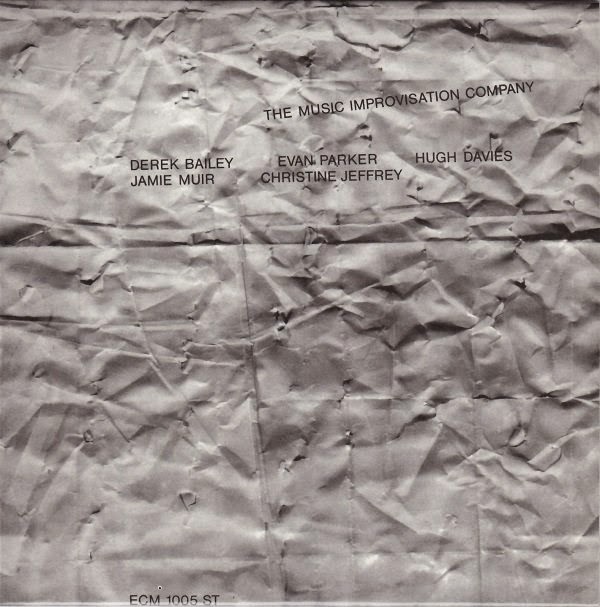

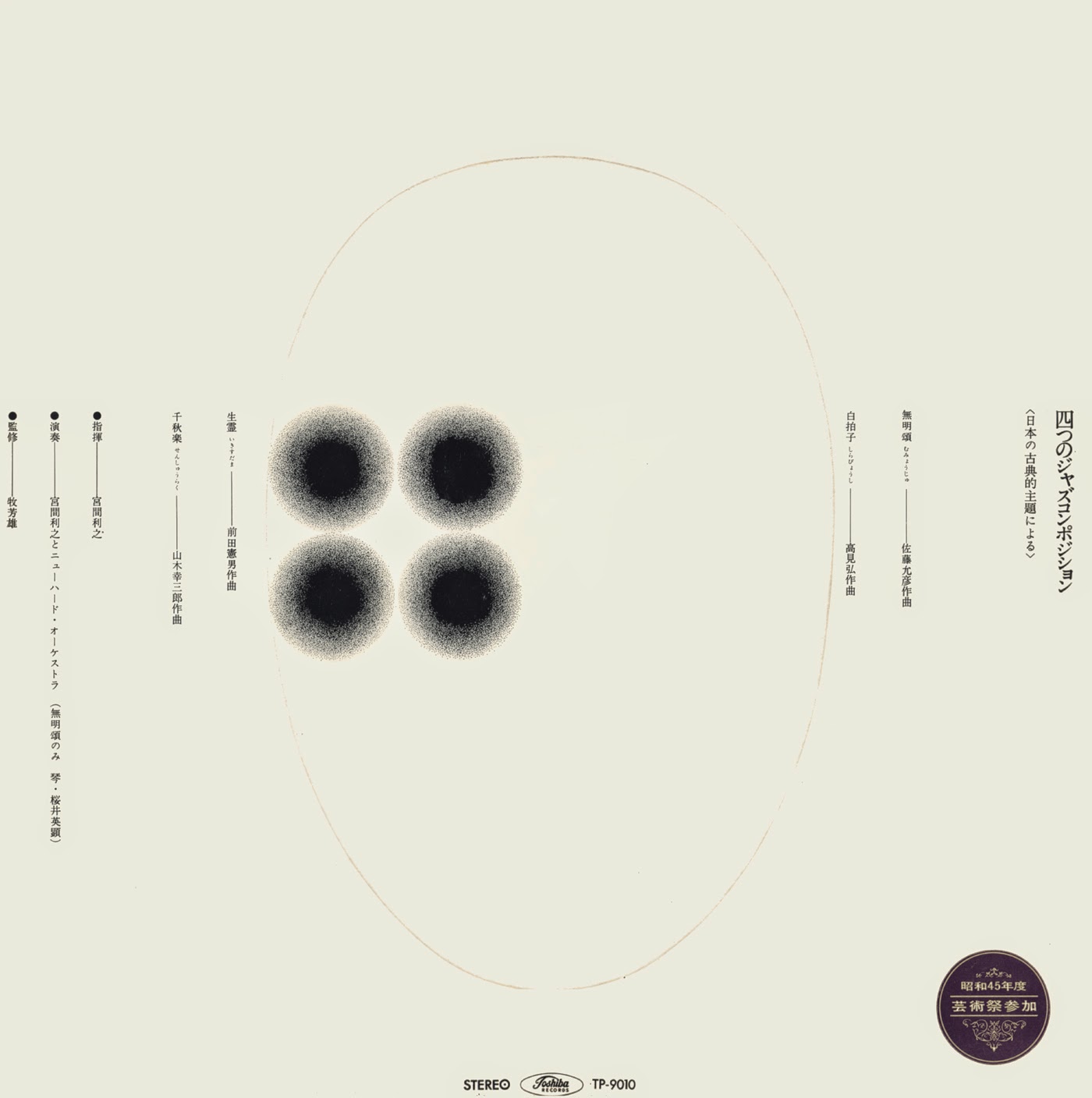

By 1965, Vitet, Chautemps, Saudrais, and Portal (then primarily a classical clarinetist) had asked Tusques to compose a number of loose springboard-pieces to work on as a group, which led to the recording of Free Jazz for poet Marcel Moloudji’s tiny Moloudji label. In company with German vibraphonist-reedman Gunter Hampel’s Heartplants (Saba, 1965) and trumpeter Manfred Schoof’s Voices (CBS, 1966), Free Jazz is among the very earliest documents of a wholly European improvised music, one which springs more greatly from regional influences than those from across the Atlantic.

Free Jazz was followed in 1967 by Le Nouveau Jazz (Moloudji), which joined Tusques with Wilen in the saxophonist’s first recorded entrée into free playing (he would continue somewhat in this vein over the next several years), backed by Guerin and itinerant Italian drummer Aldo Romano, a fixture in Steve Lacy and Don Cherry’s ensembles of the period. Both Moloudji recordings are among the rarest documents of European jazz and were limited to a pressing of only 200 copies apiece—nevertheless, it was Tusques’ wherewithal that led to the first recorded examples of avant-garde French jazz.

By the mid- to late-60s in France, improvisation took on a political edge not dissimilar to that which it had in the States. France’s involvement in Vietnam at the start of the decade, not to mention governmental maltreatment across class lines of both workers and liberalist academics at the university level, led to the revolts of May 1968 and subsequent unrest, and the New Left found sympathetic ears among the jazz vanguard. Expatriate African-American and African artists, their struggle against racial oppression viewed by the Left with a similar lens to the proletarian struggle, led to a period of broader acceptance of free jazz in the liberal French public.

Tusques, though now looking at this period as “a reflection of the attitudes and ideas of the time,” was nevertheless one of the most notoriously political of the new French jazzmen—titles for his compositions like “L’Imperialisme est un Tigre un Papier,” “Les Forces Progressistes,” “Les Forces Reactionnaires,” and Black Panther-themed works like “Portrait of Erika Huggins,” “Right On!” and “Power to the People” belie a decidedly anti-establishment sensibility. The second volume of his Piano Dazibao series on Futura featured a cover with drawings of Mao, Lenin, and Arthur Ashe in addition to Tusques; the back of the third volume of the Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra consists of drawings of the musicians interspersed with Chinese field workers.

Even if these concerns were “of the time” and not something Tusques feels a reflection of his current work, his affinity for a resurging interest in the Vienna School (Webern, Berg, Schoenberg) of composers belies a continuing political sensibility—“they were fighting fascism with their music, much as [improvisers] and artists do today.”

The first ripples of American free players began to show up on the Parisian scene in 1968, primarily due to an extreme paucity of gigs in New York and unwillingness on the part of major record companies to seriously document the music. Drummer Sunny Murray, late of the groups of Albert Ayler and Cecil Taylor, was one of the first to make his home in Paris (though saxophonists Marion Brown and Steve Lacy were making a stand as well), and that year formed his Acoustical Swing Unit with both French and visiting free players. Prophetically, its first European incarnation included Tusques, Guerin, Vitet, Portal, Jamaican tenorman Ken Terroade (previously based in London), itinerant West Indian trumpeter Ambrose Jackson, and later added expatriate Americans Alan Silva (cello), Frank Wright, Byard Lancaster, and Arthur Jones (saxophones) and Earl Freeman (bass). Tusques, with his balance of insistent left hand and pointillistic right, helped to reign in the first two official Swing Unit recording dates, two of his three with Murray. These include the eponymous 1968 ORTF concert recording released by Shandar (Sunny Murray) and its companion Big Chief (Pathé, 1969).

By 1969, as a result of offers from French labels like BYG, Musidisc-America and Pathé, a significant number of American free jazzmen had arrived in Paris for gigs and recording contracts; Tusques and his compatriots therefore had the opportunity to work with figures like Anthony Braxton, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Don Cherry and trumpeter/trombonist Clifford Thornton. These latter two were of particular importance in Tusques’ development, for as a particularly good ear-learner he fit in perfectly with Cherry’s process-based, ongoing and ear-taught approach to learning the seemingly unending and all-encompassing “Togetherness” suite. Tusques was a frequent collaborator, even assisting Cherry with some of the piano parts on the famed Mu recordings (BYG, 1969)—a series of duets with drummer Ed Blackwell. He also joined up with Thornton, resulting in what might be the valve trombonist’s strongest recording, The Panther and the Lash (America, 1970), with Guerin and drummer Noel McGhie.

It didn’t take long, however, for a significant number of gigs to dry up as the French musicians’ unions began to frown on the large number of perpetually-visiting Americans in Paris. Some, like Murray and Silva, were able to stay on, however, and it was with those two in mind that Tusques assembled his third date as a leader, Intercommunal Music, for Shandar in 1971.

Originally planned as a quartet date for piano, cello, drums and the bass of Beb Guerin, on which a number of Tusques originals would be investigated, kismet and ‘snafu’ turned it into something quite different. “I booked several hours of studio time in advance, Beb and I waited and waited for hours and we were getting very nervous because Sunny didn’t arrive. Finally, there was less than an hour of studio time left, and here come Sunny and Alan with four friends saying ‘OK, here we are, let’s go!’ We only had 37 minutes left, and I couldn’t even teach them the tunes, so what you hear on the record is exactly what happened in the studio with that time.”

What looks like one of the heaviest line-ups of free jazzmen one could conceive of—Murray, Silva, Tusques, Guerin, trumpeter Al Shorter, alto saxophonist Steve Potts (who would later join the Steve Lacy quintet), bassist Bob Reid (of multinational improvising quintet Emergency) and percussionist Louis Armfield—was, in fact, completely unexpected. An insistent, driving and minimal theme is voiced by the ensemble, leading into one of the most memorable ‘free’ alto solos these ears have heard, Tusques alternating between rhythmic repetition, roiling bass soundmasses and anthemic Maoist folk melodies, the unrehearsed group surprisingly empathetic to Tusques’ drive and whims.

Yet Tusques increasingly began to find free improvisation a musical “dead end” and found it necessary to search for other, more integrated approaches to improvisation. In addition to playing and recording a number of solo piano expositions (released to great acclaim on the Futura and Le Chant du Monde labels), Tusques formed the Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra in the early ‘70s, a meeting of French and African musicians that would yield to a “popular appeal,” something that could get both social and artistic concerns out to a number of music listeners of all stripes.

“The name comes from these things: Intercommunal, like French and Africa together; Dance, so people can feel the music; and Free, because it was a free approach to traditional music of the world.” The group included a number of African percussionists, like Sam Ateba, Cheikh Fall and Guem, as well as the great alto saxophonist from Guinea, Jo Maka; French jazzmen like trumpeter Michel Marre; German trombonist Adolf Winkler (“he could play everything—one minute J.J. Johnson, the next minute Tricky Sam Nanton!”) and Spanish orator Carlos Andreu (“he was a revolutionary poet; he would get up and pick random passages from Leftist texts, improvising upon them in concert”).

African and Latin American folk themes yield to lengthy improvisational passages filled with more ebullience than severity in this context—there are even pieces that successfully hedge dub as much as they do Breton music or kwela. The orchestra lasted throughout the rest of the decade in various guises and on into the 1980s, recording nearly ten albums for vanguard French labels including Le Temps de Cerises and Vendemiare (a subsidiary of Palm), before eventually disbanding.

Since the mid-80s, Tusques has co-led a trio with Noel McGhie and Paris bass clarinet wizard Denis Colin, in some ways an heir apparent to the altars of Portal and Sclavis, albeit with an entirely bop-based sensibility that dips into the same spring as Dolphy. This trio recorded Tusques’ Blues Suite for Transes Europeenes in 1998, and it remains his most regular working group (Tusques picks his gigs with the utmost care, so this group might not work as much as followers of his music would like).

Tusques, in collaboration with his partner, actress/vocalist Isabel Juanpera, and members of the Parisian improvisers’ community like Colin and Vitet, has previously expanded upon the “Blues Suite” in works like Blue Phédre (Axolotl, 1996) and Le Jardin des Délices (In Situ, 1992), adding an operatic (and quite possibly cinematic) scale to his already colorful small-group music.

In what might seem a departure, one of Tusques' major projects is in collaboration with architect and visual artist Jean-Max Albert, in which Monk’s compositions are investigated visually. Numbers are applied to thematic fragments, and each number has a corresponding shape—these become surreal diagrams that retain perfectly the gravity and whimsy, the yin and yang of Monk’s music, at times like a painting of Mondrian, at times like a Miró. It his hoped that a concert version of this work can be performed, with Tusques performing the pieces surrounded onstage by the visual images. Such a multifaceted view of Monk is, in many ways, a perfect analogue for the music of François Tusques: an assemblage of insular phrases yields a colorful and multi-directional oeuvre, a never-ending film of freedom, culture, and social engagement. Intercommunal, indeed.

Thanks to François, Jean Rochard and Sarah Remke of the Minnesota sur Seine Festival, and Guy Kopelowicz for making this article possible.

Related Article

Minnesota Sur Seine 2005: Intercommunal Music on the Mississippi

Recommended Listening

François Tusques, Blues Suite (Transes Europeens, 1998)François Tusques, Blue Phedre (Axolotl, 1996)

François Tusques, Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra (Vendemiaire, 1976-1978)François Tusques, Intercommunal Music (Shandar, 1971)Clifford Thornton, The Panther and the Lash (America, 1970)Sunny Murray, Sunny Murray (Shandar, 1968)François Tusques, Free Jazz 1965 (Moloudji/In Situ, 1965)

more info and some records can be bought from futura/marge(another legendary lable)

.jpg)

.jpg)